Srinagar Records ‘Warmest’ Day in 14 Year with possibility of light Snowfall

Srinagar, Jan 13 (WD):

Amid Prolonged Dry Spell, Srinagar Records ‘Warmest’ Say in 14 Years

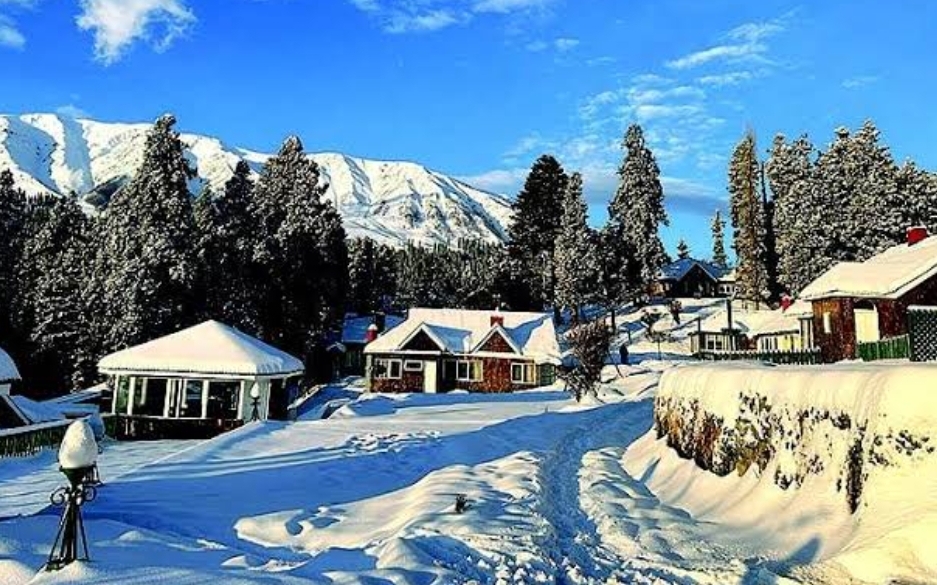

Srinagar, Jan 13 (GNS): Unusual weather pattern continues in Jammu and Kashmir this winter as Srinagar recorded maximum of 15.0°C on weekend, the “warmest” day in 14 years in the middle of ‘Chillai-Kalan’, vernacularly considered the harshest period of winter period which is ending on January 30.

A meteorological department official here told Wattan Daily Urdu/English not only Srinagar, maximum temperature at many stations recorded 6-8°C above normal with highest maximum temperature recorded over Banihal station at 20.8°C followed by Srinagar (15°C) while Jammu recorded 8.9°C.

He said today’s temperature was the sixth highest record temperature in over a century as Srinagar recorded 15.1°C on 23 January 2003, 15.5°C on 9 January 1976, 15.7°C on 31 January 2001, 15.8°C on 25 January 2010 and 17.2°C on 23 January 1902.

Many stations have recorded unusually warm temperature this season as mercury rose to 23.4°C on January 11 this year which was the highest ever maximum temperature for the place.

The weatherman has forecast the possibility of light snow over isolated higher reaches due to feeble Western Disturbances (WDs) approaching on January 16 and 20 but said that dry weather is likely to continue till January 23.

“Dry weather is likely to continue till January 23 with feeble WDs approaching on 16th and 20th evening,” the MeT official here told Wattan Daily.

Under the influence of these WDs, he said, generally cloudy weather with light snow over isolated higher reaches is expected.

From January 21-23, he said, generally dry weather is expected.

He said “redevelopment of fog with cold day conditions from tomorrow onwards till 16th January over plains of Jammu Division,” he said.

Earlier, freezing weather conditions relented considerably also with Srinagar recording a low of 0.2°C against minus 4.0°C on the previous night. The MeT official said that the temperature was 2.3°C ‘above’ normal for the summer capital of J&K for this time of the year.

Qazigund recorded a minimum of minus 2.0°C against minus 4.2°C on the previous night, he said. The minimum temperature was 1.0°C above normal for the gateway town of Kashmir, the MeT official said.

Pahalgam recorded a low of minus 0.6°C against minus 5.3°C on the previous night and it was 6.5°C above normal for the famous resort in south Kashmir.

Kokernag, also in south Kashmir, recorded a minimum of minus 1.2°C against minus 2.4°C on the previous night and the temperature was above normal by 2.44°C for the place, the official said.

Kupwara town in north Kashmir recorded a low of minus 0.3°C against minus 4.4°C on the previous night and it was 2.6°C above normal there, the official said.

Gulmarg, the official said, recorded a low of minus 1.0°C against minus 3.2°C on the previous night and the temperature was 6.9°C above normal for the world famous skiing resort in north Kashmir.

Jammu, he said, recorded a minimum of 4.0°C against 3.7°C on previous night, and it was below normal by 3.0°C for the winter capital of J&K.

Banihal recorded a low of 3.0°C, Batote 8.0°C and Bhaderwah 5.8°C, he said.

Kashmir valley is under ‘Chillai-Kalan’, the 40-day harsh period of winter, which will end on January 30. However it does not mean an end to the winter. It is followed by a 20-day-long period called ‘Chillai-Khurd’ that occurs between January 30 and February 19 and a 10-day-long period ‘Chillai-Bachha’ (baby cold) which is from February 20 to March 1.